Mohammad ibn Hassan al-Tusi, commonly known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, was a prominent 13th century scholar and an influential figure in the history of science and Islamic thought. His long list of contributions include the founding of the Maragheh observatory, a library with over 400,000 books, and many other contributions in the fields of math, astronomy, and philosophy, among others.

Born Feb. 18, 1201 in Tus, Khorasan in modern day Iran, al-Tusi began studying Arabic and the Qur’an as a child. His first teacher was his grandfather, Mohammad b. al-Hassan, who also taught him jurisprudence and hadith sciences, followed by his uncle, Nur al-Din Ali b. Mohammad, who taught him logic and philosophy. He also studied jurisprudence and hadith sciences with his father and under his guidance, al-Tusi would go on to begin the study of mathematics, perfecting the various branches.

Following his father’s death, al-Tusi would go on to fulfill his father’s wish by traveling long distances in order to seek knowledge and learn from the best. His travels would eventually lead him to the city of Nishapur which was home to some of the best scholars at the time. Within a short period of time, he achieved expertise in numerous disciplines such as mathematics, astronomy, and various fields of the intellectual sciences. He would even go on to write a few books, gaining a well-respected status among the intellectual circles of that region.

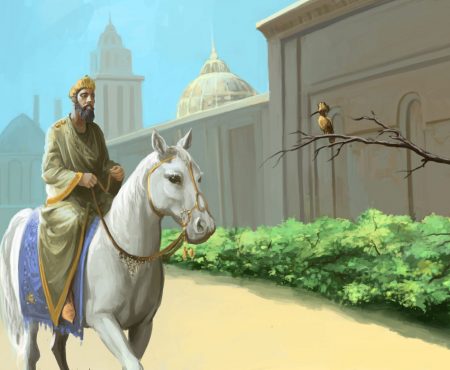

During that period, the infamous Mongol invasion led by Genghis Khan had begun, bringing about mass bloodshed with cities falling one after another, leaving people displaced and looking for other places to live. When the conquest reached the Khorasan region and Nishapur, al-Tusi took up an offer by the envoy of a ruler who admired scholars to move to a different region. Once there, he continued writing, dedicating certain works in the fields of ethics and astronomy to the local ruler.

As he further elevated his rank among the scholars of that era, news of his intellect along with the dedication of some of his writings to the local ruler reached the leader of the Ismaili government who requested that al-Tusi migrate to their region, which happened to house the most significant library in the territories under Ismaili rule. Al-Tusi accepted, although some argue that he did not really have a choice as people at the time were not in a position to refuse a ruler’s request and that he was forced to make the move. The move, however, would prove to be a good one for al-Tusi as it would clear the way for further advancement in his scholarly pursuits. While in the Ismaili territory, al-Tusi spent his time teaching, researching, and writing scholarly material. Throughout that time, he would move up in that society’s ranks while maintaining close contact with fellow scholars and members of the academic world. He would become known as ‘The Scholar’ very early on.

Following the second, more brutal invasion of the Mongols led by Hulagu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, the Ismaili government would fall and everyone, including their leader, would be killed except for al-Tusi and a couple of physicians due to Hulagu Khan being aware of their scholarly significance. Al-Tusi was once again left with no choice, but to join the Mongol government as a scientific advisor.

With the ethnic cleansing of Muslims and an estimated 40 million people killed during the Mongol reign, the lives of many Muslim scholars, intellectuals, and academics were threatened, and most of the libraries and books of that period faced the threat of being burned down to ashes. As an advisor to the Mongols, al-Tusi strived to save the lives of many scholars while preserving valuable books and writings. During that period, he established the Maragheh observatory in order to conduct research while housing many notable scholars and scientists from various countries during that period. He also built a nearby library which carried over 400,000 books. Not only were lives and valuable assets saved, research from the observatory continued until long after his death, resulting in many original contributions in math and astronomy which would inspire and benefit future generations.

Part of his research at the Maragheh observatory resulted in a precise table on planetary movements. His book “Treasury of Astronomy” contains the famous “al-Tusi couple” which is a geometric production creating rectilinear motion from one point on a circle rolling into another. Al-Tusi’s creation was a successful reformation of Ptolemy’s planetary models, constructing a method in which all orbits are defined by a static circular motion. Many historians of astronomy believe that the planetary models developed by al-Tusi at the Maragheh observatory made their way to Europe, offering Copernicus inspiration for his astronomical models.

Al-Tusi produced many writings throughout his lifetime. According to some sources he authored over 180 scholarly writings in a variety of subjects including mathematics, astronomy, medicine, popular sciences, philosophy, logic, ethics, jurisprudence, history, theology, and literature.

Following his death, two of the Mongol emperor’s sons converted to Islam which was followed by the Mongol government turning into an Islamic government.

He passed away on June 25, 1274 in Baghdad while on a mission to retrieve some books that were looted.

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was buried on the outskirts of Baghdad at the Kadhimiya Shrine, as requested in his will. Also, in his will, was a request to avoid mentioning his political and intellectual standing on his grave stone. Instead, he asked that a part of chapter 18, verse 18 of The Holy Qur’an be written on his grave stone which reads, “and their dog (lay) outstretching its paws at the entrance”. It is worth mentioning that he is buried at the entrance of the Kadhimiya Shrine.

All comments (0)